Food Sensitivities & Allergies

Food sensitivities and allergic reactions to food are increasing in Westernized societies—the rates have almost doubled in the last 20 years(1). To make matters even worse, not only have the rates doubled, the severity of the reactions seem to have gotten worse. It is fair to say that something is going on.

First, let’s define some terms—it has been many patient’s experience that if they are not precise in using some medical terms, some in the medical profession may latch on to that imprecision and use it to dismiss the patient’s condition—you know “You are NOT allergic to gluten because your skin test tells me you are not. Now, here, take this anti-depressant and don’t call me for 6 weeks!”

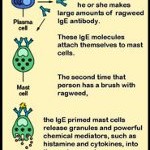

An allergic response (Figure 1) to food is defined as one where a type of immune protein, IgE (an antibody), is produced that reacts with that food1. At the end of a chain of reactions when IgE is present, histamine is released from cells—and the result may be itching, hives, respiratory symptoms such as wheezing or shortness of breath, a tightening of the throat or hoarseness, watery eyes, a runny nose and a host of other symptoms which may include abdominal pain or discomfort, swelling around the eyes, mouth and tongue, cramping, nausea, diarrhea, dizziness and vomiting. There is no absolutely definitive lab test that will always diagnose a true food allergy. The most common true food allergies are to peanuts and other tree nuts (walnuts, pecan, almonds), shellfish, milk, eggs, soy products and wheat1.

Food intolerance or sensitivity may involve the immune system but it doesn’t involve the IgE/histamine system. In fact, some will define “food allergy” as being either IgE-controlled or non-IgE controlled; food intolerance is non-IgE controlled and isn’t the “traditional” allergic response to foods (IgE-controlled). It may involve other arms of the immune system—for example it may involve IgG, IgA and/or IgM antibodies, but not IgE. Food intolerances may also involve missing enzymes—for example, those who are lactose intolerant are missing an enzyme (lactase) which helps break down and digest lactose, the type of sugar in milk.

Symptoms of food intolerance are not as immediate as food allergies but include—you guessed it—nausea, stomach or abdominal pain, gas, cramping or bloating, vomiting, heartburn, headaches, diarrhea, runny nose, itching, respiratory symptoms and skin rashes.

So, clinically, food allergies and food sensitivities have similar symptoms, but a food allergy is very fast and is controlled by an IgE/histamine response. Food sensitivity or intolerance is slower to develop and may be controlled by an IgA/IgG/IgM response. Simple, right?

There are a number of theories as to why food intolerance/sensitivities are on the rise. These include:

Genetics and family history—your unique genetic background may determine what food sensitivities or allergies—if any—you may develop. For example, a child will have a 7 times greater risk of having a peanut allergy if their parent or sibling has an allergy to peanuts1.

The Hygeine Hypothesis3,1,2—as humans, we have co-evolved with our gut bacteria. While for many people, it’s an “ewww” moment to think about, these gut bacteria are incredibly important to our health. For one thing, they are absolutely essential for helping the immune system react appropriately to, and absorb food properly. Where do these bacteria originally come from? They come from our environment and when we are ultra-careful about “germs”, our children may not be exposed to the right bacteria at the right times. There is evidence, for example, that children raised on rural farms have a decreased risk of allergic disorders including eczema, asthma and hay fever4,5.

Early introduction of solid foods and/or formula feeding (as opposed to exclusive breast feeding for the first 6 months to a year). The jury is still out on this as far as the evidence—there are conflicting studies3. It is likely that it is not simply the early introduction of solid foods that can explain the increase in food sensitivities.

Combined factors: It is more likely that an early introduction, formula feeding, combined with a family history and an imbalance in gut bacteria populations all share a role in the development of both food allergies and food sensitivities. We live in a contaminated and polluted world and it is becoming increasingly evident that there are fewer and fewer conditions caused by a single factor.

If you have been dealing with gluten sensitivity, you already know the general approach to dealing with food sensitivities—process of elimination. Often, people with gluten sensitivities have other food intolerances and allergies as well. The more you can eliminate other sensitivities, the better you and your family will feel. It’s not an easy (or inexpensive) way to go, but it can make a real difference in your health! Stick with whole, unprocessed foods – organic foods as much as possible. This will limit your exposure to pesticides.

Limiting household allergens can help as well— furnace or air-conditioning filters can minimize dust and animal dander. Take a quality probiotic every day—or eat 1-2 servings of yogurt with active cultures every day. Using non-synthetic building materials and furnishings can help too. The fact is, you can control only so much in your life—but the more you limit your exposure to other potentially sensitizing products, the greater the favor you will be doing yourself and your family.

[hr]